|

Flight of the Nancy Boats May 8-31, 1919

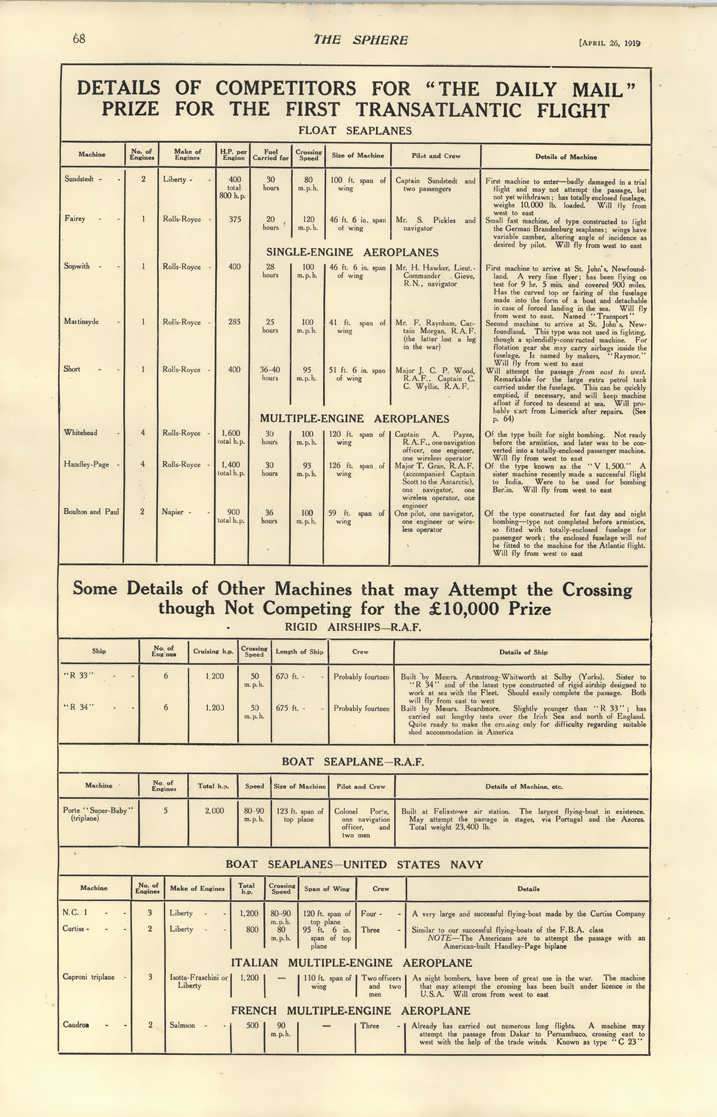

We're coming up on the centennial of one of the great milestones in human history. Sadly, it's an event that's almost forgotten today. At the end of WWI, the military nations of the world had boatloads of

new technology that was no longer needed for war, but maybe had peacetime

application. Topping the list was aircraft technology, which had developed

very rapidly during the war and was now a magnificent solution looking

for a problem to solve. One of the first goals was to cross the Atlantic

by air. At first, it was just a question of derring-do. The UK paper Daily

Mail offered a 10,000GBP prize for first flight across the Atlantic. That

sum of money and the available pile of war surplus aviation components

attracted a lot of dreamers. A long list of adventurers set out to be first

across the Atlantic.

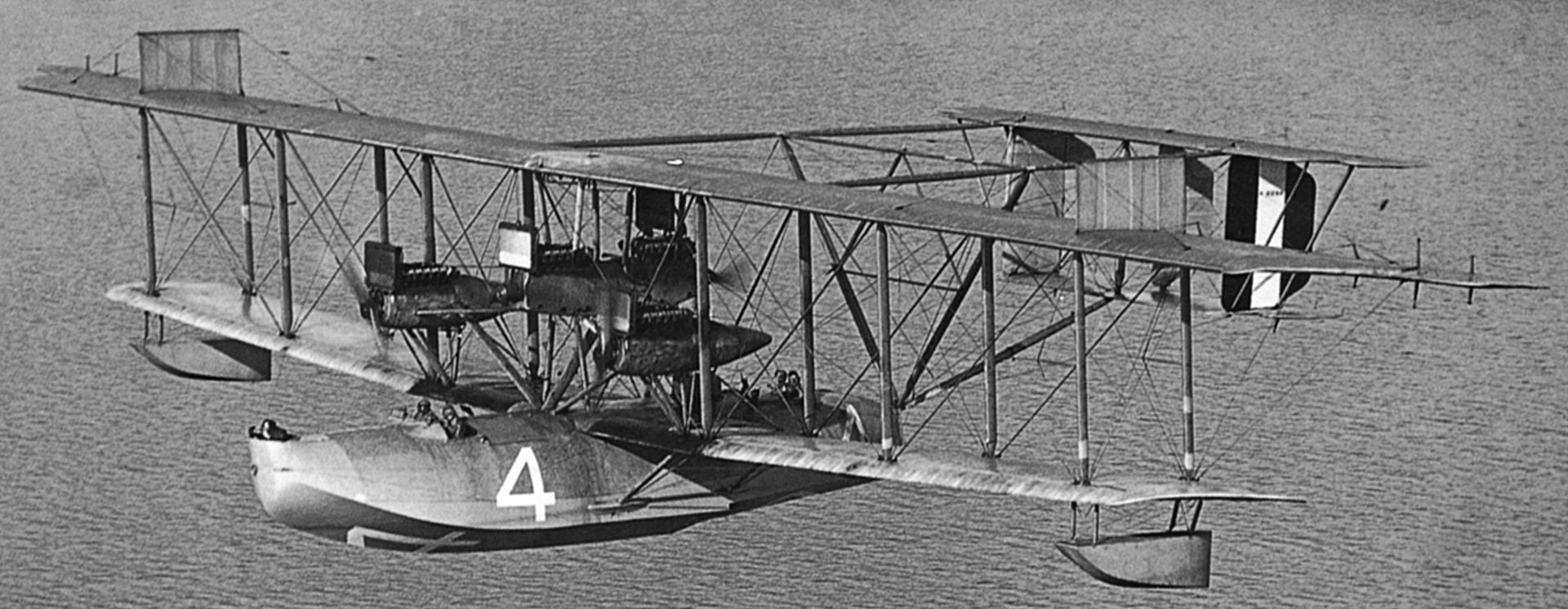

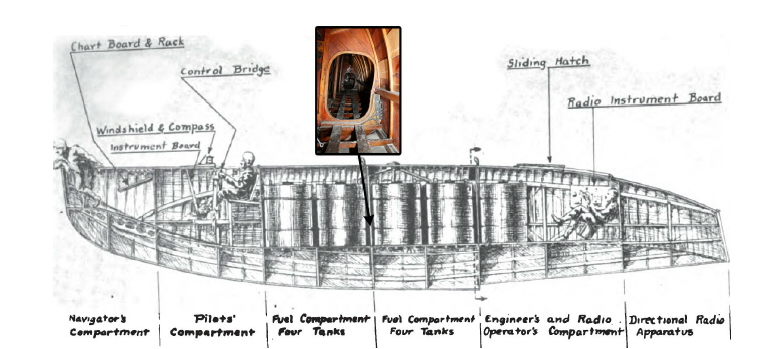

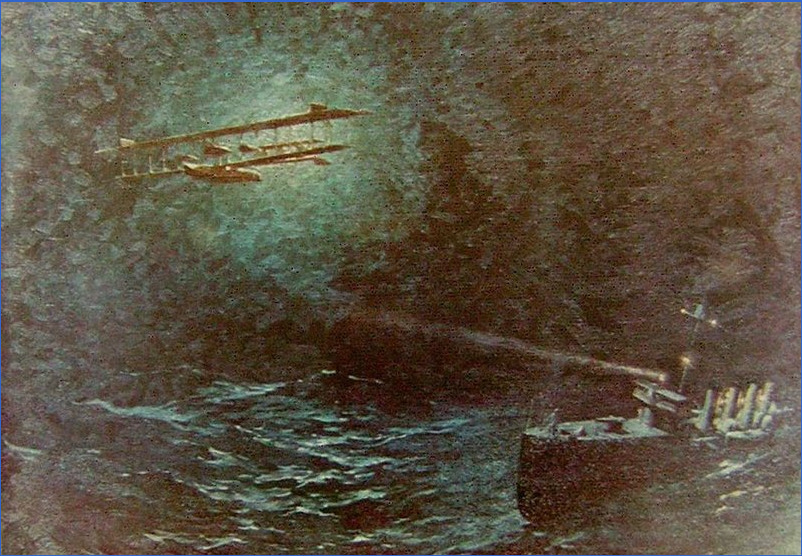

Among the US military, there was a feeling that the US should be not only be first across, but should be the dominant power in transoceanic aviation. Prizes and one-off, ill-prepared flights were the wrong way to go. Transatlantic flight was expected to have great commercial value for mail and passengers, and there was strategic value in dominating that business. The strategic part was that commercial transatlantic flight would produce experience and technology that would be needed in the event of a war. During the recent war, the super weapon had been the U-Boat. Having control of the ocean skies was seen as the way to nullify the U-Boat threat in future wars. There were aviation proponents in the Army and the Navy who presciently predicted the role of air power. And so the US Navy set out to be the dominant force in transatlantic aviation. While intrepid adventurers flung themselves into the air, only to disappear in the nasty green Atlantic, the Navy set out to develop safe, dependable technology to enable repeatable transoceanic flight. Eventually this would win the honor of first across for the US Navy, but at the time their very expensive new technology and expansive manpower only earned the sneers of derision when compared to the knightly adventurers who followed in their wake. That's why you've probably never heard of it. The first thing you need for a transoceanic flight is an airplane. And

the Navy wanted a great big airplane. The Navy partnered with Glenn Curtiss

to develop not one, but a fleet of flying boats. The knickname of the project,

Nancy, derives from the model designation of the aircraft...Navy-Curtiss,

or NC. These flying boats were biplanes, built the way you would expect

a 1919 biplane to be built...out of spruce and doped linen. The thinking

at the time was that over-water aircraft should be flying boats in case

they had to touch down to fix a balky engine. And so the crew pod and floats

were made the way you would make a boat...mahogany frames with an aluminum-over-plywood

skin. Doesn't sound like much, but these were BIG planes, among the largest

biplanes ever built. The wingspan was 120 feet, which is larger than a

737! The planes would be powered by four advanced Liberty engines, each

producing 400HP. Four planes in total would be built, and since this was

an experiment, each plane had a different engine configuration: one plane

would have engines wing mounted abreast as you would expect. Another would

have two pairs of wing mounted engines, one of each pair operating as pull

and one as push. Another would be a trimotor. The configuration that worked

best was four engines, three pulling and one behind the center motor pushing.

All four boats were modified to this standard. Not only could this plane

cross oceans, it could function as an immense fighter-bomber for anti-submarine

warfare.

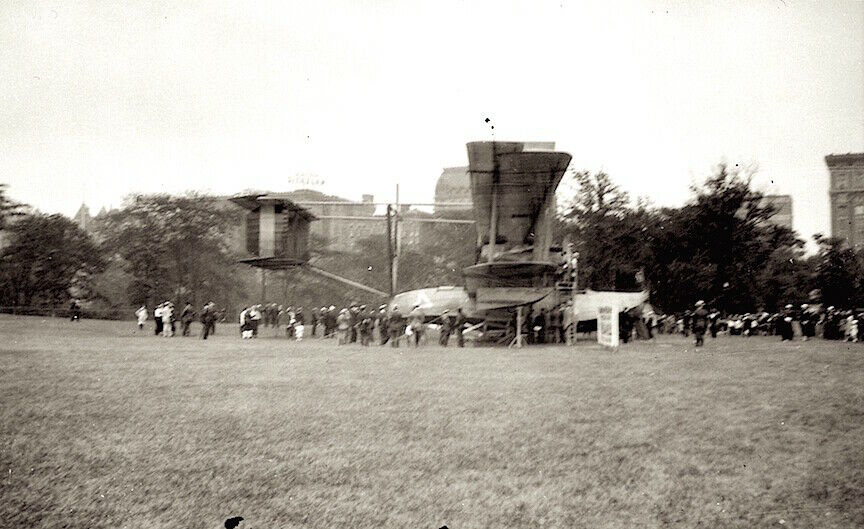

Many new techniques were needed to build a plane this large. Curtiss

ran out of room at Hammondsport, and portions of the plane had to be built

at various facilities around the country. Curtiss relocated airframe assembly

to Garden City, and the Navy insisted that portions of the assembly be

subcontracted in order to reduce development time. Interchangeable parts

and subassembly integration had been part of military procurement since

Eli Whitney. But this was the first time a military airplane was built

from subcomponents built by different manufacturers. For example, the giant

spruce wings were built by Locke & Co, a custom carriage company better

known for building bodies for Packard, Lincoln and Franklin. Locke was

located on 58th Street in New York. Imagine a 120 foot wing being loaded

on a purpose built cart and dragged through the streets of Manhattan and

over the Brooklyn Bridge. To accomplish this feat, the wings were

transported in the middle of the night, with police closing streets and

roads the whole way to the Rockaway Naval Air Station. The Rockaway aerostation

is one of New York's lost airports. It's now Jacob Riis Park, across the

channel from Floyd Bennett Field, which is yet another of NY's lost airports.

Simply having a plane isn't enough to cross the Atlantic, especially

if you're aiming for repeatable success. The first problem was navigation.

Sextants and such as used on a ship pose certain problems in the air. For

one thing, you are moving very fast. There's a lot of vibration and air

movement. And it's not obvious where the horizon is. So the NC's carried

a radically new set of navigation instruments. This included a sextant

with an artificial horizon, altimeters, drift gauges, compasses, and the

most up to date radio direction finders. For the most part this technology

gradually became obsolete, but the experience set the groundwork for all

modern aerial navigation. To back up the navigation system, the Navy obligingly

strung out it's soon to be mothballed battle fleet at 50 mile intervals

along the route. If the navigation tools failed, all the pilots would have

to do is find the next ship. The ships could send up flares and star

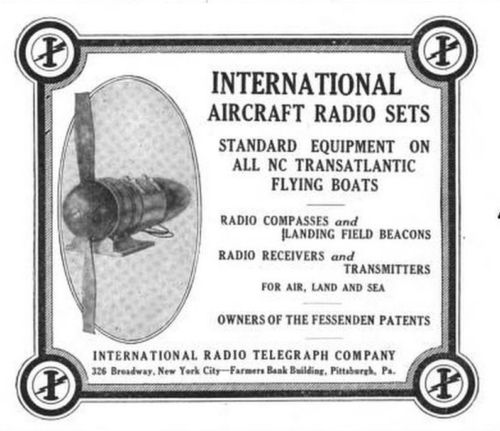

shells if the planes drifted off course. Finally, true radio telegraph

technology had emerged by this time, so each plane was equipped with not

one, but two radios. The main radio used a 200 foot antenna that was extended

like a fish line when the plane was in flight. Unfortunately, it was powered

by a windmill mounted on the wing. This would prove to be a problem during

the flight, when two of the planes were forced to make emergency landings.

On the surface, the backup radios could only broadcast using small batteries

and short lengths of antenna. this would reduce range and make the radios

useless when they were most needed.

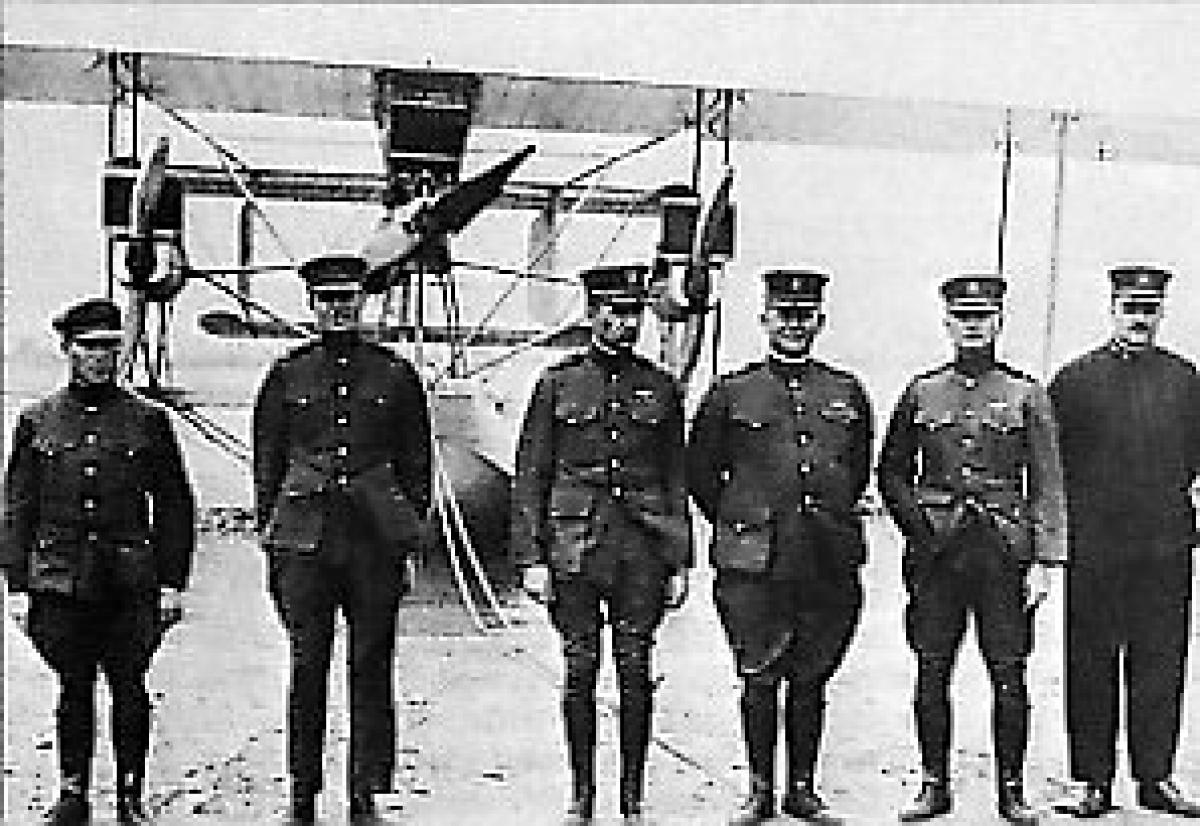

And the crew. These were big planes, with big crews. Each crew had a

commander, two pilots, a radioman, a flight engineer and a navigator. Bear

in mind that as big as these planes were, they had open cockpits. The planes

were large enough to have some sheltered space inside the crew pod, but

the commander, navigator and pilots sat out in the weather.

And speaking of weather, the weather posed no small problem. Weather over the Atlantic is legendary for being awful. But in 1919, there was total ignorance about weather conditions at altitude. To develop the route and schedule, the Navy fielded a small fleet of weather ships, equipped with blimps and weather balloons. A whole host of launch and recover technologies was developed to produce high altitude weather reports. Of the four planes prepared for the mission, NC-2 had to be cannibalized

for parts during trials. The three remaining planes set off for Newfoundland

May 8, 1919. In Newfoundland, various repairs were made while waiting for

favorable weather. They finally lifted off for the Azores on May 16. Travelling

at 80mph, they arrived at their destination the next day. But NC-1 missed

the last few signal ships and had ditched it's radio in order to lift off.

It landed some 20 miles north of the Azores. Searchers located the plane,

but all they could do was rescue the crew before it sank. NC-3 landed just

a few miles south of it's objective, and had to sail the currents like

a boat for about 120 miles before hitting land. Unfortunately, it was pounded

by high seas as couldn't complete the mission. NC-4 was the fastest of

the planes, and luckily arrived in better weather. It was able to reach

port. Refreshed and refueled, it continued on to Lisbon on May 27, becoming

the first airplane in history to complete a transatlantic crossing. It

finally arrived in Plymouth on May 31, having taken 23 days to fly from

New York to England. From there, the plane was disassembled and returned

to the US, ironically on the USS Zeppelin, a prize ship taken during the

war.

Meanwhile, what about all the other adventurers who were trying to beat the NC's? Since the US Navy wasn't eligible, the Daily Mail prize was awarded to Alcock and Brown, who made a direct dash from Newfoundland to Ireland in a Vickers on June 14, 1919. A consolation prize of 5,000GBP was also awarded to Hawker and Grieve, who crashed their Sopwith into the Atlantic and were given up for dead before they were found days later bobbing around in a life raft. One more attempt is worth noting. As the Nancy's awaited repairs at Newfoundland, the Navy revealed that

it had an insurance policy. Navy Blimp C-5 arrived on May 10, set to follow

the destroyer line to Europe. The blimp had been modified so that

it could burn some of it's hydrogen as fuel to extend its range. Unfortunately,

the weather that held the NC's in Newfoundland tore C5 from its moorings

and the fill had to be released. The remains of the ship were carried away.

At the time, the entire effort was derided as being expensive, over

staffed, and over supplied. Compared to the madcap stunt of flinging yourself

across the ocean in a tiny plane, flying a squadron across the ocean accompanied

by something like 80 naval vessels seems easy, if not totally frivolous.

And so it was newsworthy for a moment, then quickly forgotten. But it bears

emphasizing that this was 1919, the wings and control structures were made

of wood and cloth, not one part of these machines was dependable in any

modern sense, navigation was experimental at best, and the challenges of

wind and weather across the Atlantic completely unknown. It took a lot

of guts to get into one of these crates and fly across the Rockaway channel,

much less across the ocean. But the Navy wasn't setting out to impress

people or win prizes, it was trying to develop dependable technology and

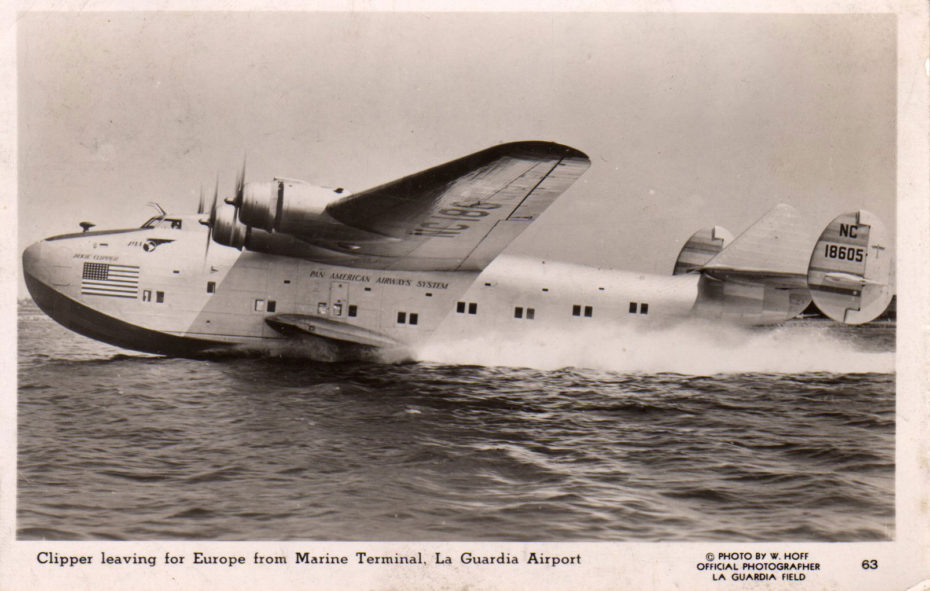

repeatable success. And it was an outstanding success. The same techniques,

including picket ships and weather balloons, and the very same route was

used when the first Pan Am flying boat went into regular service between

NY and the Azores. No surprise, since Juan Trippe was a contemporary Naval

aviator and crossed paths with the NC project as the flight was being prepared.

The NC boats continued on in military service. A total of ten

were built and were used for a decade as shore patrol and rescue craft.

NC-4, the last survivor, was gifted to the Smithsonian, which has

never had sufficient space to put it on display. It's housed at the Naval

Air Museum in Pensacola. The NC fliers were fetted in Portugal. When they

arrived in the UK on May 31, they were swept into the welcome festival

for Hawker and Grieves who had just returned from their rescue at sea.

They didn't even get their own parade. And by the time they arrived back

in the US, Alcock and Brown's nonstop flight had eclipsed them in the news.

They were received at NY City Hall and Glenn Curtiss hosted a fine dinner

for them at the Commodore. Then they went back to their Navy or Coast Guard

careers. Many years later, Lindbergh crossed the ocean and was awarded

a Congressional medal for his solo flight. This prompted a bill in Congress

to award the NC fliers medals for their earlier achievement. The special

awards were presented in 1929, ten years after the flight of the Nancys.

Lindbergh himself had this to say: "I had a better chance of reaching Europe

in the Spirit of St. Louis than the NC boats had of reaching the Azores.

I had a more reliable type of engine, improved instruments and a continent

instead of an island for a target."

So that's the story. Almost forgotten, but not without lessons for the ages. References: First Across by Richard K Smith, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD 1973 Triumph of the NC's by Westervelt Richardson and Read, Doubleday, New York 1920 (Link) First Flight Across the Atlantic by Ted Wilbur Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 1969 (Link) Links: Developing the NC Flying Boats Progress is fine, but it's gone on too long NC 4, First Across the Atlantic History of the Curtiss NC 4 Flying Boat Videos: Newsreel: Newfoudland to Lisbon US Navy: The Great Flight of the NC 4 First Crossing The 1919 NC Transatlantic Expedition NC-4 at National Naval Aviation Museum Copyright©2019 MFrank |